I’ve finished 1919, the first part of M. The Son of the Century. Scurati does an amazing job of showing how Mussolini was able to turn Italians’ discontent into authoritarianism.

I wanted to share some background information that could be helpful for non-Italians who are reading the book.

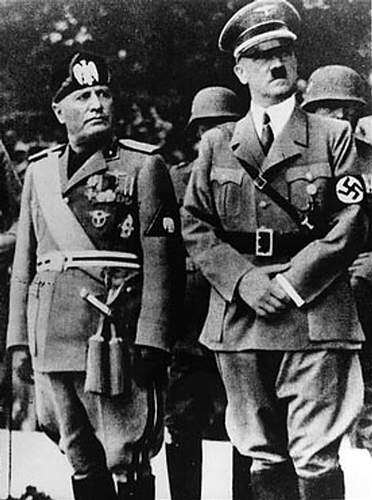

Who was Mussolini?

Benito isn’t an Italian name. It’s the Spanish version of Benedict. For example, it’s Bad Bunny’s legal name. If you’re curious, the equivalent Italian name is Benedetto, which is what Pope Benedict XVI is called.

Carla’s family tradition notwithstanding, Benito is not a common name. Generally, Italians are less likely than English speakers to give their children foreign names. There are some names like Mirko or Jessica that have become common enough that they may not even be perceived as non-Italian. But generally, you won’t find the diversity of names among ethnic Italians that you would in an American kindergarten.

So how did he get that name? Benito Mussolini was named after Benito Juárez, the first indigenous president of Mexico. Juárez is a beloved figure in Mexican history. To this day, you can see his quote, El respeto al derecho ajeno es la paz (“Respect for the rights of others is peace”) around the country.

Mussolini was born and raised in Emilia-Romagna, the region I used to live in. It’s historically a left-leaning part of Italy. In fact, one of the nicknames for Bologna, the region’s capital, is la rossa (“the red one”), in part because of its association with socialism.

His parents were themselves socialists and chose the name Benito in honor of Juárez’s legacy. Crazy, isn’t it? The inventor of fascism was named after a famous native Latin American leader.

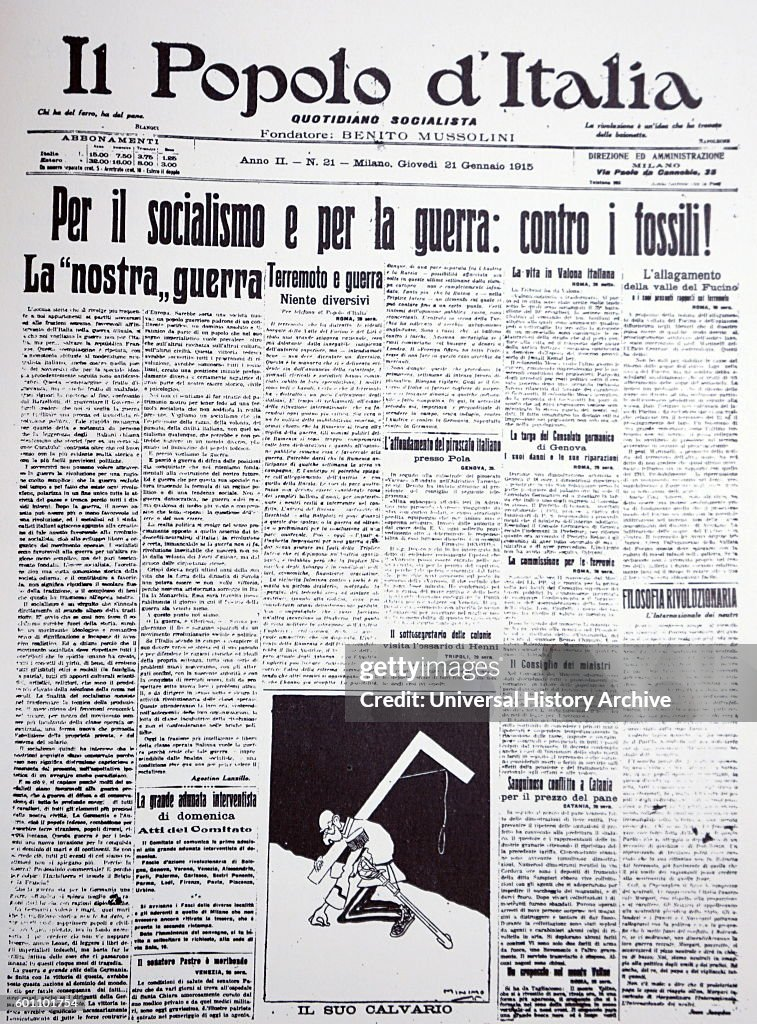

When World War I broke out, Mussolini was the editor of Avanti (“Forward”), a widely read socialist newspaper. Initially, he sided with the socialist party’s position of neutrality, but later flipped completely and became the most outspoken socialist voice for intervention in the war. As a result, he was expelled from the party. He pretty quickly developed a new revolutionary ideology and founded the newspaper Il Popolo d’Italia (“The People of Italy”).

Why were people so angry?

Before WWI, Italy was part of the Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary. When war broke out, Italy remained neutral. Some groups, like the socialist party leadership, argued that the country should stay out of the fight. Others, like Mussolini, wanted the country to join on the part of the Triple Entente. Why? Pro-intervention socialists thought it was a good chance to smash old empires, while other Italian groups wanted to seize territory and expand the size of the kingdom.

The background is that Italy didn’t exist as a united country until the middle of the 19th century. Unlike other European countries like France or Portugal, there had never been a king of Italy. To form the kingdom, Victor Emmanuel II and his supporters annexed various territories that had been controlled by local or foreign leaders.

The issue was that “final” borders that were defined in 1861 didn’t include several regions that had large Italian populations. In particular, there were areas in the Alps and along the east side of the Adriatic Sea with Italian-majority towns nestled in ethnically mixed regions.

Italy did end up joining the war on the side of the Triple Entente in accordance with the Treaty of London. This secret agreement promised Italy these “missing” territories in case of victory.

After the war, Italy failed to get all the promised land. As a result, there were a lot of Italians left to wonder what they had fought for. At the same time, the Austo-Hungarian Empire did fall, and the Russian Revolution was successful, so socialists saw a clear path to taking down the monarchy.

Where is Fiume, and why did people care about it?

Fiume (pronounced in two syllables, roughly “FYOOmay”) is the Italian word for river. The town is still there and is lovely. Only, it’s generally known as Rijeka, which is Croatian for river. It’s directly east of Istria, a peninsula that is today mostly part of Croatia. It’s a little more than an hour by car from Trieste, a city that is now in Italy. Before WWI, it was part of the Austro-Hungarian empire.

In 1919, Italians formed the largest ethnic group in the city but were not the majority. For that reason, Italians like Mussolini claimed it, along with Dalmatia, for Italy.

I’ve been to Rijeka. I took a trip there on my own when I was living in Bologna. I was struck by how Mediterranean it felt and how friendly everyone was. I remember seeing njoki on restaurant menus and wondering whether that was a recent addition to the local cuisine. At one point, I asked a local guy for directions. Rather than explain to me how to get there, he walked me where I needed to go, chatting with me in a mix of English and Italian. When I remarked that it was impressive that he’d learned those languages so well in school, he told me hadn’t—he had studied German and picked up other languages from TV and movies.

Who were the arditi?

Ardito (plural arditi) means brave or courageous. They were special forces formed during the war. Armed with daggers and grenades, they were known for charging across the battlefield to reach enemy lines.

In my opinion, Scurati is excellent at showing how these men had grown used to extreme violence and were disappointed by the outcome of the war. Additionally, Scurati suggests many times that veterans in general felt like they had been cast aside at the end of the war, rather than praised for their sacrifices.

What comes next

This section, 1919, ends almost like a horror movie. The socialists sweep the elections, and the referendum in Rijeka is a failure for D’Annunzio. Mussolini is contemplating giving up journalism and trying out a different career.

We came so close to avoiding fascism! I’ll keep writing here as I make my way through the book. Message me if there is anything you’d like me to touch on.